Synopsis

This critical journal aims to explore the mechanisms and effects of contemporary digital technologies on human sensorial relation to ‘reality’. The paper comprises three main chapters. The first chapter establishes the existence and analyses the experience of Networked Space as the new space within which reality is constructed via the ubiquitous presence of the internet. The second chapter describes the mechanisms of interactive interface technologies as the tools which mesh virtual reality with physical reality, and analyses the ways in which they design containment. The third chapter is a personal response, in the form of a proposition, of an alternative way of seeing, whereby I use the term ‘anarchitecture’ as an artistic approach of intervention to disrupt and reimagine the architecture of networked space.

Table of Contents

I. List of Illustrations (3)

II. Introduction (6)

III. The Internet as a Hyperobject (9)

IV. Engineering the border between the Virtual and the Real (15)

V. Art: a glitch in the screen – Digital Anarchitecture (21)

VI. Conclusion (26)

VII. Bibliography (27)

This critical journal aims to explore the mechanisms and effects of contemporary digital technologies on human sensorial relation to ‘reality’. The paper comprises three main chapters. The first chapter establishes the existence and analyses the experience of Networked Space as the new space within which reality is constructed via the ubiquitous presence of the internet. The second chapter describes the mechanisms of interactive interface technologies as the tools which mesh virtual reality with physical reality, and analyses the ways in which they design containment. The third chapter is a personal response, in the form of a proposition, of an alternative way of seeing, whereby I use the term ‘anarchitecture’ as an artistic approach of intervention to disrupt and reimagine the architecture of networked space.

Table of Contents

I. List of Illustrations (3)

II. Introduction (6)

III. The Internet as a Hyperobject (9)

IV. Engineering the border between the Virtual and the Real (15)

V. Art: a glitch in the screen – Digital Anarchitecture (21)

VI. Conclusion (26)

VII. Bibliography (27)

“We travel

in bubbles, upon which the face of the world is projected through a 360º curve,

thereby floating through space without feeling the space itself. We flatten our

sense of depth whilst simultaneously witnessing its expanse.”

the Theory of the Bubble, 2015

the Theory of the Bubble, 2015

It dawned upon me once, at the

age of 16, that my senses, namely my eyes, were strained by the rupture between

the visual screen and physical reality. I walked away from my screen to a

neighbouring field and sat there and tried to focus. But the blurry image of

the hills took a while to become a sharp image, and the feeling of being within

a space took a while to assert itself over the feeling of watching an image of

a space. I eventually went back to write these thoughts down, which I then titled‘The theory of the Bubble’. The file stayed untouched over the years,

until recently. During the COVID-19 pandemic and first lockdown, I eerily

stumbled upon Hito Steyerl’s lecture “Bubble Vision” whereby she describes a

relationship to reality where one is “at the centre of the scene, everything

revolves around [them], and yet [their] body is missing from the scene”[1].

It wasn’t the first time that I found texts and works that drew me back to my bubble

theory. But it suddenly became clear that I should do something with it now,

dig deeper inside of the surface that I was touching upon. It seemed that

someone like Steyerl had done so, having created a whole body of work exploring

the cultural regime of the senses imposed by our contemporary technological

infrastructures.

Born in 1999, on the brink of the 21st century, I have witnessed the accelerated permeation of digital cultures and infrastructures. These are not objects that I take for granted. I hold dear within my memory the event in which a student in my primary school did a presentation on the first iPad, and how amazing it was to think of a flat touch screen through which to work, entertain, and connect with the rest of the world. Now, about a decade later, I find myself watching Mark Zuckerberg give me a presentation about the metaverse, where the mobile internet will be replaced by a dematerialized internet, one in which being ‘online’ consists of teleporting yourself to a simulated reality where the physical reality will be duplicated in a more fantastical form[2]. It is apparent that the borders between the virtual and the ‘real’ are engineered to be increasingly blurred (although real is a term that I will contest in this critical journal). One’s sense of belonging online is merged with their sense of belonging offline, and it is not as clear as simply turning a switch on and off. ‘World’ then embodies both spaces at once through a grey zone of contact where one can leap in and out of dimensions of sensorial awareness, dissociating from reality whilst also realigning with reality. Reality then alters into a space of infinite possibility and distortion, a collage of elements that may not even go together within the logical laws of physics. When one travels between the virtual and the ‘real’, like I did when I went from screento physical space, one “drops the illusion of perspective in favour of “instant sensory awareness of the whole”, by means of disconnecting from the immediate space to connecting to the internet world beyond[3]. This world, or altered reality, is a green screen. A flat unidentified surface whose material can be changed, whose depth can be reversed, whose physical properties can be altered and engineered to serve any purpose. As Steyerl puts it, Man is at the centre of a stage, or bubble, where reality is simulated through an engineering of sensual cruelty, that, I argue, distorts man’s capacity to differentiate between the realand the virtual. What gets lost in translation when consciousness travels from one side to the other? What gives me or denies me access to the real? What becomes of human awareness when its consciousness evolves in a world where senses are constantly bouncing between the material and the immaterial? Between presence and absence?

By stating that the world is a green screen, I am first establishing the meta-absence of ‘world’ to challenge the notion of ‘reality’. My artistic task here, then, is and has been to “establish what phenomenological experience is in the absence of anything meaningfully like a ‘world’” at all[4].

The translating mediators between the virtual and the real are the interfaces through which we connect and disconnect. Namely, as of now, all screen devices. Their interfaces are designed to facilitate the accessibility and travel between the two dimensions, or two interconnected ‘areas’ of everyday life. Although, I don’t like to describe this texture as the relationship between two places, as a binary reality, because it is not one or the other, but rather a whole system in itself … even though the experience of it is cognitively incoherent. Interface technologies are just the ground from which the border between offline and online is raised, blurred and dematerialized. They are not digital space itself, but aim to translate the internet offline, implying that it exists in a spatial dimension[5]. The online internet then moves offline, becoming an environment rather than just an interface. Interfaces are the medium or technology that have introduced this “new scale into human affairs”, which I will try to illustrate, understand, and which form the tools of my artistic practice[6]. It is therefore the point of contact, the point of interaction, and of communication, that I am most interested in. Through the mediums of new media art and interaction design, I have attempted to reorder and play with the dialectics of networked space as being itself a medium for art. In order to uncover the grey area between the worlds that digital technologies create within and between us, as users and beings, I am making networked space my primary medium via the technologies which engineer it and which sustain its architecture.

The Internet as a Hyperobject

[the new scale of human affairs]

In Timothy Morton’s book Hyperobjects: Philosophy and Ecology after the End of the World, he coins the term “hyperobject” to refer to things that are “massively distributed in space and time relative to humans”. He goes on to say that “a hyperobject could be a blackhole, [or] the Lago Agrio oil field in Ecuador, [or] the Solar System, [or] the sum-total of all nuclear materials on Earth, [or] just plutonium, [or] the product of direct human manufacture, [or] just plastic bags”[7]. It follows that climate change is a hyperobject, or the erosion of the Louisiana swampland is a hyperobject. In all these examples, “local manifestations of the hyperobjects [are] not the hyperobjects themselves”[8]. By nature, then, hyperobjects are invisible, immaterial, things we cannot quite grasp, and yet “they can be detected in a space that consists of interrelationships between aesthetic properties of objects”[9].

The internet, then, can be qualified as a hyperobject. It manifests itself in a multiplicity of ways that make it seem familiar, accessible, and tangible. It is a place of memory making, of identity making, of creating a sense of belonging. Yet, if one were to ask someone what the internet is or where it is, one will more often than not offer quite a vague response. The internet is difficult to grasp and difficult to point at just like global warming or the speed of light. The internet “has no shape, […] has no face, just this name that describes everything and nothing at the same time”[10]. However, we seem to know that it is there, as though it is a place to go to, a reality that calls us in through signals and notifications. But is that enough to guarantee that it exists? We find ourselves at a dead end of cartesian thought. Cogito, ergo sum may no longer be supported within a context where the means of knowing extend the means of ‘existing’ things. For, “the internet does not exist” in itself, yet it does through its local manifestations of its infrastructure as a hyperobject[11]. The current malaise of the western world may best be explained by the extinction of one of its ontological pillars. As expresses Nam June Paik, “nowadays, Descartes would throw himself in the Seine in order to preserve his virginity of cognition”[12].

Virtual reality, as previously described in conjunction to physical reality, is therefore not a space in itself, but the sum of spaces created from the local manifestations of the hyperobject, the internet. The architecture of the internet is a systems architecture, like the roots of plants or the veins of the body. It is a network, and not a final destination. It is a circuit of routes with many junctions and stops where one is hypnotized by a sense of control in navigation. The point of entrance is a white light, and the point of exit is a black hole. It is a vacuum where physical “objects […] appear to become translucent and strangely compressed until they finally disappear altogether”[13]. Morton goes on to say that hyperobjects “generate space-time vortices, due to general relativity”[14]. As one receives a notification and instantly turns on the screen, one penetrates the depth of a mirror which has its own phenomenological properties separate from those of the physical scale, such that “things are themselves but we can’t point to them directly”[15]. When one decides to exit that virtual space which is locally manifested by the screen, or the notification, one then re-enters the appearing world of objects. One then decelerates from the speed of light. This new scale introduced by the medium of the internet makes it so that the “gap between phenomenon and thing yawns open, disturbing [ones] sense of presence and being in the world”, for in fact it is not a single scale that is introduced, but the tension created by cognitively incoherent scales of reality whose border is instantly traversable[16].

![]()

Fig. 2

c = 3 × 108 m/s (The Speed of Light)

The instantaneity of adaptation between different temporalities and spaces, facilitated by interactive interface technologies, does not allow consciousness to discern the border between them, but rather upholds a hybrid reality where virtual and real exist together. As the internet eliminates space, one is both there and not there. Pure duration is then ruptured, for pure duration is “the form taken by the succession of our inner states of consciousness when our self lets itself live, when it abstains from establishing a separation between the present state and anterior states”, or states that are not occurring in the same ‘location’[17]. Once, my therapist told me that the brain could not tell the difference between virtual events and real events, when trying to explain the mechanisms of chronic anxiety. The ontological experience of what is ‘here’, or what is offline, can be merged with the experience of things happening far away, or online, as they merge into the belief system of the mind. The local manifestations of the internet construct a ‘world’ space that is then experienced as a green screen, a flat surface whose depth is simulated, upon which we can appear or disappear, be simultaneously present and absent, via the diversion that the mind takes within the reality spectrum. It follows that this mind belongs to a body whose borders oscillate and twitch. Like in dreams, the narrative of everyday life is disjointed and incoherent, although emotionally and experientially believable, or held as ‘true’, within the architecture of the dreamscape. We can see ourselves from above and from within. Similarly, we can see the world from space and all angles – just like when one looks over the planet on Google Earth as one should be falling but instead hovers over the ‘world’ (whose original body is constantly updated and reimagined). This is a state of free fall, as Steyerl describes, because we are away from any gravity force. We are never really landing back to a firm ground upon which to base reality. She goes on to say that “this disorientation is partly due to the loss of a stable horizon, [and that] with the loss of a stable horizon also comes the departure of a stable paradigm or orientation, which has situated concepts of subject and object, of time and space, throughout modernity”[18]. If this is true of the subjective experience it may also be true in the formulation of culture. Like the speed of light, history as a collective narrative is compressed into a single simultaneous experience, resulting in its fragmentation and disorder, suggesting an alternative temporality altogether. Linear space and time as a cohesive movement within the fabric of reality has been replaced by the simultaneity of a multiplicity of perspectives and speeds, in the form of the rhizomatic structure of the internet. Mark Fisher describes this as a Cyberspace-time crisis, where one has to opt-out of cyberspace rather than opt in, imposing the internet’s parameters of space and of time[19]. Reality, for Fisher, is by definition “a form of collective dreaming” which, in the 21st century, is experienced through the stress between “the infinity of cyberspace” and “the finitude of the organism”[20]. Networked space is the space of reality and yet it is primarily characterized by an elimination of space altogether, precisely because it is infinite. This paradox is what makes it a hyperobject.

Steyerl makes the point that ‘reality’, or this consensual hallucination, is image, so much that “this means that one cannot understand reality without understanding cinema, photography, 3d modelling, animation, or other forms of moving or still image” for “image and world are […] just versions of each other”[21]. The green screen is a reality of postproduction, where “the world can be understood but also altered by its tools […] : editing, colour correction, filtering, cutting, and so on, […] as the means of creation of images and of the world in their wake”[22]. As we are eternally falling through images, reality flashes by to the point of blindness: “This is not simply white light. It is the result of too much information. Too much equates to nothing”[23]. Like in Sugimoto’s long exposure shots of cinemas, where “the architecture of the space is lit predominantly by the residual light of the erased film”, the architecture of our everyday life is predominantly lit by the residue of a succession of sensorial flashes at high speed, which cancel each other out, resulting in a void[24]. Even though falling entails movement, by virtue of it being eternal it is also stagnating. Virtual reality, as the texture of the green screen, can then be defined as “the removal of a single human shaped mass from the fabric of the universe”, for existing at the speed of light demands of us to not ‘exist’ at all[25]. Such as the Japanese Olympics of 2021 where stadiums were void of human beings due to the COVID pandemic, or such as Zuckerberg’s metaverse, suggesting that one needs to enter the virtual plane in order to exist, leaving whole cities void of human presence. Hyperobjects such as the internet, as Morton argues, have therefore brought about the end of the world: the world is left as a green screen[26].

![]()

Fig. 3

“Every desire

is an end

and every end

is a desire

then

the end of the world

is a desire of the world

what type of end do you desire?”

Sun Ra

![]()

Fig.4

Engineering the border between the virtual and the real

[designing containment: feedback loops as closed circuits]

The blurring of the border of what is obviously virtual and what is obviously real is grounded in the idea that reality is a spectrum. This is best illustrated by the following diagram where we can identify different degrees of reality. It goes from the ‘real world’ to ‘augmented reality’ (AR), to ‘augmented virtuality’ (AR), to ‘virtual reality’ (VR). All of these realities put together are identified as ‘mixed reality (MR)’[27].

![]()

Fig. 5

![]()

Fig. 6

This spectrum is actuated via interactive interface technologies. They are the point of contact between us and the abstract body of the internet, rendering the things that we can’t grasp somehow accessible and translatable to our minds. It is via their language that we have a shared sense of space in the embodied internet. As the brain cannot tell the difference between the virtual and the real, images or virtual events transcend us in the form of memory just like physical reality does. They include screens, sensors, cameras, 3D sound, machine learning, and so on. It follows that the interaction designers, engineers, and owners of the means of production of such interface technologies are those that determine the way in which we communicate with the immaterial and virtual world, or what Mark Fisher would call the “ghosts” of ourselves[28].

Interactive interfaces are asserted through their association to both progress (future) and endlessness. One can ask themselves what iPhone we are at in the same way one asks themselves what year it is. And yet at the same time, it is easier to imagine the end of the world than the end of capitalism in the same way that it is impossible to imagine the end of the iPhone (or other associated technologies of permanence). As such,

“endlessness can be seen as a culturally and ideologically manipulated phenomenon, when linked to and produced by technologies of modernity and capital that have vested interests in the mythological maintenance of their own structures as flexible forms of permanence”[29].

Even though interface technologies are products that we buy, they have also become the necessary means of communication and of societal participation. We are biopolitically policed in seemingly indiscernible ways, making the interests of surveillance bond with the economic interests of behavioural prediction, such as data mining. This form of policing, of establishing the impossibility of bypassing rules within a regulated virtual space, is biopolitical in the sense that it touches upon the realm of body and mind at a sensorial level because the internet is established as an ‘uninterrupted interface’, and therefore is “a perpetual test of the subject’s presence with his own objects”[30].

The trouble begins, as David Rokeby states, as soon “as the user’s awareness of the interface ends, in the true “Narcissus style of one hypnotized by the […] extension of his own being in a new technical form”[31]. In Rokeby’s web essay Transforming Mirrors, he offers a coherent explanation of how interactive technologies engineer containment within users and audiences. Through looking at their mechanisms, one can better understand how the world as a green screen, as flat and absent of depth, can simulate an illusion of depth and of consequentiality, thus hypnotizing the user. He compares interactive technology to mirrors, stating that a technology is interactive to the degree that “it reflects the consequences of our actions or decisions back to us”, thus providing us with a self-image[32]. A feedback system is therefore created between the re-action of the user and the mirroring of the interface, resulting in an echo and a simulation of depth within the flat surface.

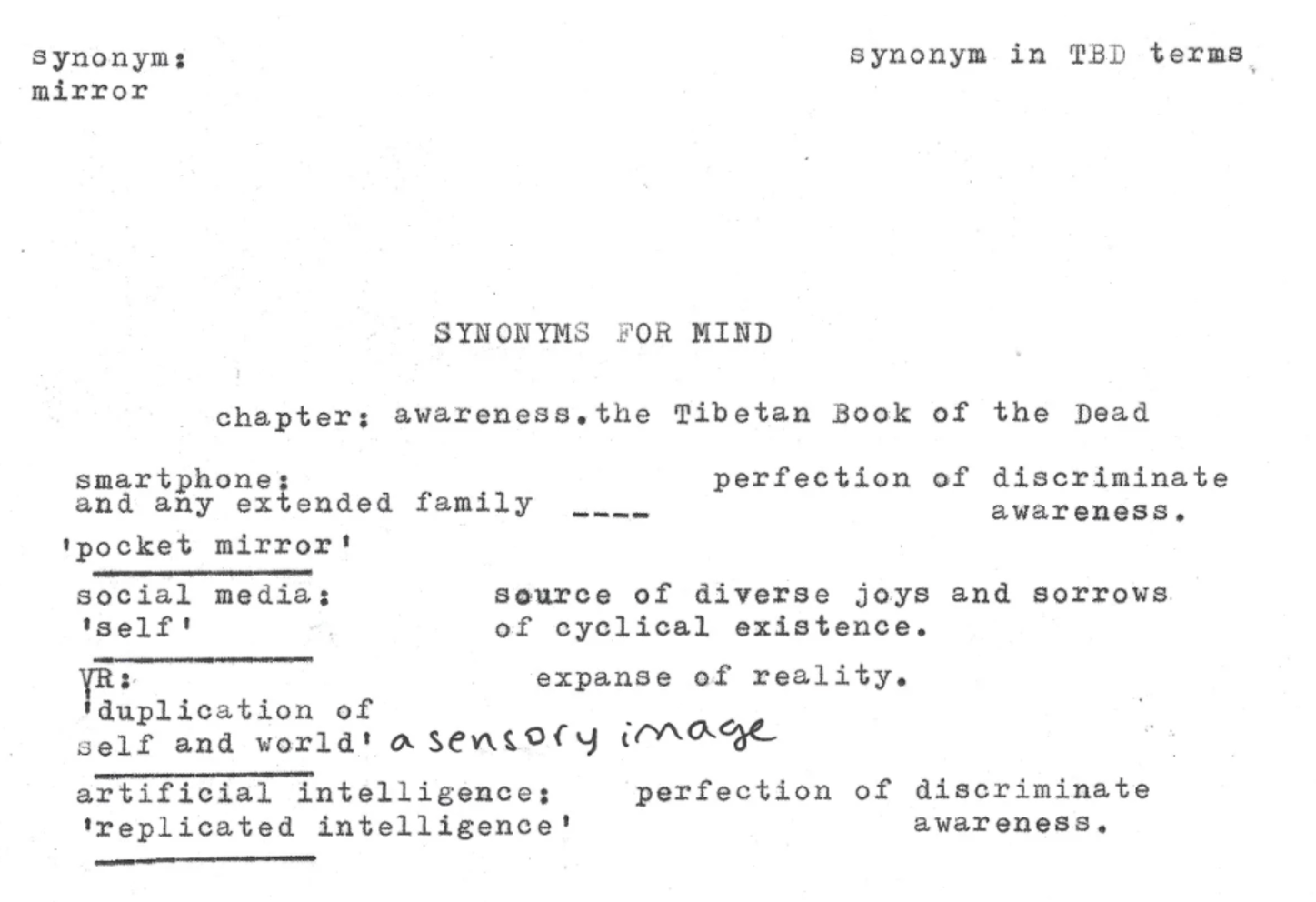

In the Tibetan Book of the Dead (TBD), written in the 8th century AD, there is a passage entitled ‘awareness’, where synonyms for ‘mind’ are offered. Some of these include definitions such as “perfection of discriminate awareness”, or “expanse of reality”. In my own exploration of the ontological implications of Rokeby’s Mirrors, I decided to make ‘mirrors’ another synonym for ‘mind’. I then attributed interactive interface technologies with different definitions of mind offered by the TBD.

![]()

Fig. 7

The smartphone is a ‘pocket mirror’ that slides into one’s hand and which can be pulled out at any time, where one can be immersed in a dimensional virtual space through a flat surface. It is an object of “perfection of discriminate awareness” as the world that it contains has a strict system of segregation of modes of participation within social life and reality. It mirrors us and our sense of participation in the ‘world’. Equivalently, the evolution of AI is also a form of discriminate awareness, for it is trained to distinguish, and even emulate, objects of reality via truths or falsehoods. Therefore, AI replicates intelligence in an attempt to mirror the mind’s ability to differentiate reality (‘truth’) from what is not real (‘false’). Social media is a mirror in the sense that it is the realm of the self-image. It is a source of ‘diverse joys and sorrows of cyclical existence’, another definition by the TBD when describing the mind. These are just some ways in which interface technologies act as extensions of ourselves by virtue of mirroring the mind.

When the mind as mirror communicates with an interactive, mirroring, interface, it is the same as placing two mirrors in front of each other. Rokeby describes this phenomenon as a stereoscopic tension, whereby “the tension that exists between these two points of view is resolved by the brain into the revelation of depth”[33]. Like an echo endlessly repeating the same image, feedback is created via the closed-circuit system of mirroring interaction and validating the original image of world. As Nam June Paik states, “[feedback] is the bread and butter of electronic culture” and it “never occurs in an open circuit: closed cycle is the unconditional pre-requisite for this happening”[34]. As such, as each person sees himself as “an astronaut in his capsule”, reality inside the bubble is made up of closed circuits and feedback systems that create an illusion of depth, of dimension, of consequentiality, of ‘being there’. The engineering of this simulated depth is what sustains the mind in an uninterrupted hypnotic state where the virtual and the real meet, and where the tension is resolved. When two mirrors meet, the image of infinity unfolds, but it is nonetheless nothing more than an image. Even if you try to jump into the open space offered by the mirror, you will still hit your head against a wall. As such, interactive technologies act as mirrors that create feedback loops which create white noise – like when there is sound feedback and the sound replicating itself accumulates to an endlessly high pitch, or like when two cameras face each other and the colour spectrum accumulates to create an infinitely white square. Too much equates to nothing, resulting in “the active assembly of nobody in order to see nothing”[35].

In an attempt to explore this ‘magic trick’, I used a now widespread interactive interface and communication technology on another living being: Zoom. Zoom is an interactive interface that flourished as a consequence of crisis and is culturally associated to crisis. In fact, the ‘world’ as we know it, still in the midst of COVID-19, is a world where zoom is widespread as a communications technology. I had never heard of zoom prior to this crisis (which turned out to be used as a surveillance technology). What Zoom reveals is what Steven Shaviro argues in his essay on accelerationist aesthetics, namely that “crises do not endanger the capitalist order”, rather they help it, “phoenix-like”, to renew itself[36]. In this sense, the capitalist technocracy is renewed via another form of perceptive subversion.

With this in mind, I created a zoom call between four devices whose cameras and microphones were all pointed at a pig. The devices ‘spoke’ to each other via the feedback created from the sounds of the pig. What happened was that the pig actually held its head up to listen to this sound that it kept hearing, as though there was something there. Rummaging around and smelling around, whenever the feedback got loud enough it would stay still, as though asking ‘who is there?’. But what was there was just the pig itself.

![]()

Fig. 8

Interactive technologies engineer containment in exactly that way: by creating the illusion of something ‘being there’ when in fact it is only the reflection of ourselves. Or it is that we gravitate towards erasing ourselves in order to establish that we exist. As such, we travel in a simulation of time, of movement, of self-realization, when in fact the world we are referring to as exterior to ourselves is just the traces of ourselves that we leave behind. Zuckerberg encourages the perpetuation of his empire in a celebration of the ingenious invention of the metaverse by saying that “you’re actuallyinside the experience, not just looking at it”, as if physical reality couldn’t already offer us that possibility[37]. And yet what is important to remember is that “there is no absolute absence, only presences made of different substances and consistencies”[38].

Art: a glitch in the screen – Digital Anarchitecture

Poor images, low-fi content, digital junk, errors leading to alternative and autonomous spaces – my medium is grey matter, a bridge between light and absence of light, a fog, a blur, no resolution, no depth. If there was a ZAD[39]on / in the internet, what would it look, feel, smell, sound like?

First, to establish that it is all real. It is not just a question of articulating the virtuality of the internet as a hyperobject that one should then think that it isn’t real. It is just that the terms to reality no longer apply in the same way. As Morton states, “for all humans as we transition into this age of asymmetry, there are real things for sure, just not as we know them or knew them”[40].

Right: Fig. 10

Digital space is not a smooth surface. In fact, it is often prone to errors, to crevices, to possibilities of diversion. It is first crucial to understand its mechanisms in the same way that it is crucial to become aware of the interface in order to realize its flatness. As Rokeby states, the interactive artists “holds a mirror to the spectator” in order for the spectator to become aware of themselves. The interactive artist is akin to the description of Tehshing Hsieh in his year long performance whereby he becomes “a body lacking temporal continuity and physical integrity, a body whose borders oscillate and twitch, yet whose gaze in the ruins of visibility, holds its observer remorselessly in its grip, as if to say it is you I am implicating here”[41].

In a few of my own video works I have often played with first person perspective, similarly to video games. I have documented and staged the subjective experience of contemporary life through its task-performing movement, individualized isolation and interpretation of reality. In a video that I called Ocean, I placed a GoPro on myself and followed a group of people into the sea. This is an interactive video work, whereby the image reacts to sound. The sound piece is glitchy and ambient and uses the rhythms of the waves and the underwater soundscape to equate the sensation of drowning to the sensation of losing ground. As the video plays, the image distorts itself according to the sound. And thus, it feels as though the protagonist, who is paralleled to the spectator, is (are) drowning in the mass of a spatial glitch.

![]()

Fig. 11

I have always had an aesthetic attraction towards low quality digital images. When watching video footage of 9/11 on camcorders, I couldn’t help but feel a parallel between some of the low-quality images of catastrophe with the images of drowning in my Ocean video piece. It seems that in both cases, these are documentations of an obliteration of time and space, or of ‘world’. As Steyerl describes in her Defense of the Poor Image, “poor images […] express a condition of dematerialization”[42]. In the 9/11 documentation, it is as if this specific frame is the image of the end of history, or the western world. In the Ocean video, it is also a scene of time and space ending.

![]()

Fig. 12

It is not so much the aspect of catastrophe that becomes important, but the texture of reality falling apart – or to reveal what reality is made of. When the seemingly permanent textures of reality reveal themselves as fragile, vulnerable, and prone to mistakes, one may break away from the hypnotic assumption that these structures are indestructible. In a practice of digital anarchitecture[43], one may claim power over the ways in which the networked space is dictated, constructed, and how it travels through us. This first begins with awareness. No one or nothing is in total control over an outcome, like in code, where you may give a set of rules to follow which may generatively create something completely unexpected. That technologies may bare within their mechanisms space for improvisation and chance, and therefore offer a means to assert “inassimilable values” to an otherwise perfectly ordered and predictable world. Like in age old drum patterns, where polyrhythms merge together to create rich and multi-layered music, one then discovers that out of something simple is born something so complex and alive. In asserting that digital space is a medium for art one asserts that it cannot be ignored or separated from anything called ‘reality’. In asserting that digital space is real, one can become more aware of the interface that they are a part of and interact with. By claiming an awareness over one’s sensorial experience of living, one can then finally confront the seemingly immaterial texture of reality that surrounds and penetrates them. One can orient themselves again in space, with depth. One can finally see again.

![]()

Fig. 13

Conclusion

In this critical journal, I have attempted to articulate the ways in which we experience reality when digital technologies are blended within all of its dimensions. In an acknowledgement of this digital reality, which is chronically changing faster than I may be able to describe, I have illustrated the mechanisms through which contemporary technologies work, and through which they dominate our sensorial landscapes. As a result, I have articulated some of my own reflections upon the matter as a means to give shape to the seemingly immaterial. I have established that digital space is a space which can be occupied by virtue of it occupying us, in the same way that physical space can be disputed, transformed, and reimagined. I am not so much offering a solution, but rather an alternative way of seeing, one which may best allow to remain aware and sensitive to the rapidly evolving textures of everyday life. First and foremost, to acknowledge that it is real, and that it is happening right now.

[1] Bubble Vision. 2018. [video] H. Steyerl. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=T1Qhy0_PCjs.

[2] About.facebook.com. 2021. Welcome to Meta | Meta. [online] Available at: <https://about.facebook.com/meta?utm_source=Google&utm_medium=paid-search&utm_campaign=metaverse&utm_content=post-launch> [Accessed 2 November 2021].

[3] McLuhan, M. and Gordon, W., 2015. Understanding Media. Berkeley, Calif.: Gingko Press, p.8.

[4] Morton, T., 2017. Hyperobjects. Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press, p.3

[5] Steyerl, H. and Aikens, N., 2014. Too Much World: Is the Internet Dead?. Berlin: Sternberg, p.1.

[6] McLuhan, M. and Gordon, W., 2015. P 7.

[7] Morton, T., 2017. P.1

[8] Morton, T., 2017. P.1

[9] Morton, T., 2017. P.1

[10] 2015. The Internet Does Not Exist. Sternberg Press (e-flux journals), p.7.

[11] 2015. The Internet Does Not Exist. Sternberg press (e-flux), p.1

[12]2019. We Are in Open Circuits : Writings by Nam June Paik. MIT Press, p.279.

[13]Morton, T., 2017. P.11

[14] Morton, T., 2017. P.11

[15] Morton, T., 2017. P.11

[16]Morton, T., 2017. P.12

[17] Hsieh, T. and Heathfield, 2008, A., n.d. Out of now - the lifeworks of Tehching Hsieh. MIT press, p.21

[18]Steyerl, H. and Berardi, F., n.d. Free fall. e-flux journals. P.4

[19]Mark Fisher - Cybertime Crisis. 2020. [video] https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=zOQgCg73sfQ: Mark Fisher Cyberfield.

[20] Mark Fisher - Cybertime Crisis. 2020. [video]

[21] Steyerl, H. and Aikens, N., 2014. p.6.

[22] Steyerl, H. and Aikens, N., 2014. p.6.

[23] Hsieh, T. and Heathfield, 2008, p.33

[24]Hsieh, T. and Heathfield, 2008, p.33

[25]Bubble Vision. 2018. [video] H. Steyerl.

[26] Morton, T., 2017, p.2

[27] Gupta, V., 2021. Preparing for a New Reality: Augmented and Virtual Reality. [online]

[28] Fisher. M., 2009. Capitalist Realism: Is there no alternative? Winchester: O Books. P.13

[29] Hsieh, T. and Heathfield, 2008, p.33

[30] Baudrillard, J., 1997. The Ecstasy of Communication. P.127

[31] McLuhan, M. and Gordon, W., 2015. p.14.

[32] Rokeby, D., 2021. David Rokeby : Transforming Mirrors. [online] Davidrokeby.com. Available at: <http://www.davidrokeby.com/mirrorsintro.html> [Accessed 3 November 2021].

[33] Rokeby, D., 2021. David Rokeby : Transforming Mirrors. [online].

[34] 2019. We Are in Open Circuits : Writings by Nam June Paik. MIT Press, p.301.

[35] Hsieh, T. and Heathfield, 2008, p.35

[36] Shaviro, S., 2015. No speed limit. Minneapolis: University of Minnesota press. P.42

[37] About.facebook.com. 2021. Welcome to Meta | Meta. [online]

[38] Hsieh, T. and Heathfield, 2008, p.37

[39] Zone à Défendre (Zone to Defend) – French experession that refers to the autonomously occupied zone of Notre-Dame-des-Landes in France. According to the dictionary, it is defined as an “area whose development is planned for an alternative period” (feminine).

[40] Morton, T., 2017, p.2

[41] Hsieh, T. and Heathfield, 2008,p.35

[42] 2013. Hito Steyerl. The wretched of the screen. New York: Sternberg Press. P.40

[43] In reference to artist Gorden Matta-Clark, who coined the term anarchitecture, most known for his radical interventions on abandoned buildings, reshaping and cutting through their physical structures.

List of Illustrations

Fig.1: Magritte, R., 1936. la Clef des Champs. [Oil on canvas].

Fig. 2: Rafman, J., 2008. 9-eyes. [Google Street View].

Fig. 3: Sugimoto, H., 2014. Teatro dei Rozzi, Siena "Summer Time". [Analog Film Photograph].

Fig. 4: All That's Interesting. 2019. Inside The Ghost Cities Of China That Feel Like An Eerie, Futuristic Dystopia. [online] Available at: <https://allthatsinteresting.com/chinese-ghost-cities> [Accessed 13 January 2022].

Fig. 5: Gupta, V., 2021. Preparing for a New Reality: Augmented and Virtual Reality. [online]

Fig. 6: Gupta, V., 2021. Preparing for a New Reality: Augmented and Virtual Reality. [online]

Fig.7: Lene de Montaigu, 2020. Synonyms for Mind. [ink on paper]

Fig. 8: Lene de Montaigu, 2020. Zoom 92212838368. [video]

Fig. 9: Magritte, R., 1936. la Clef des Champs. [Oil on canvas].

Fig. 10: Steyerl, H., 2010. STRIKE.

Fig. 11: Lene de Montaigu, 2020. Océan. [video]

Fig. 12: N.J. Burkett reporting as Twin Towers begin to collapse on September 11, 2001. 2001. [video] https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=oCPVNLLo-mI: Eyewitness News ABC7NY.

Fig. 13: Matta-Clark, G., 1975. Conical Intersect. [Black and White Photograph].

Born in 1999, on the brink of the 21st century, I have witnessed the accelerated permeation of digital cultures and infrastructures. These are not objects that I take for granted. I hold dear within my memory the event in which a student in my primary school did a presentation on the first iPad, and how amazing it was to think of a flat touch screen through which to work, entertain, and connect with the rest of the world. Now, about a decade later, I find myself watching Mark Zuckerberg give me a presentation about the metaverse, where the mobile internet will be replaced by a dematerialized internet, one in which being ‘online’ consists of teleporting yourself to a simulated reality where the physical reality will be duplicated in a more fantastical form[2]. It is apparent that the borders between the virtual and the ‘real’ are engineered to be increasingly blurred (although real is a term that I will contest in this critical journal). One’s sense of belonging online is merged with their sense of belonging offline, and it is not as clear as simply turning a switch on and off. ‘World’ then embodies both spaces at once through a grey zone of contact where one can leap in and out of dimensions of sensorial awareness, dissociating from reality whilst also realigning with reality. Reality then alters into a space of infinite possibility and distortion, a collage of elements that may not even go together within the logical laws of physics. When one travels between the virtual and the ‘real’, like I did when I went from screento physical space, one “drops the illusion of perspective in favour of “instant sensory awareness of the whole”, by means of disconnecting from the immediate space to connecting to the internet world beyond[3]. This world, or altered reality, is a green screen. A flat unidentified surface whose material can be changed, whose depth can be reversed, whose physical properties can be altered and engineered to serve any purpose. As Steyerl puts it, Man is at the centre of a stage, or bubble, where reality is simulated through an engineering of sensual cruelty, that, I argue, distorts man’s capacity to differentiate between the realand the virtual. What gets lost in translation when consciousness travels from one side to the other? What gives me or denies me access to the real? What becomes of human awareness when its consciousness evolves in a world where senses are constantly bouncing between the material and the immaterial? Between presence and absence?

By stating that the world is a green screen, I am first establishing the meta-absence of ‘world’ to challenge the notion of ‘reality’. My artistic task here, then, is and has been to “establish what phenomenological experience is in the absence of anything meaningfully like a ‘world’” at all[4].

The translating mediators between the virtual and the real are the interfaces through which we connect and disconnect. Namely, as of now, all screen devices. Their interfaces are designed to facilitate the accessibility and travel between the two dimensions, or two interconnected ‘areas’ of everyday life. Although, I don’t like to describe this texture as the relationship between two places, as a binary reality, because it is not one or the other, but rather a whole system in itself … even though the experience of it is cognitively incoherent. Interface technologies are just the ground from which the border between offline and online is raised, blurred and dematerialized. They are not digital space itself, but aim to translate the internet offline, implying that it exists in a spatial dimension[5]. The online internet then moves offline, becoming an environment rather than just an interface. Interfaces are the medium or technology that have introduced this “new scale into human affairs”, which I will try to illustrate, understand, and which form the tools of my artistic practice[6]. It is therefore the point of contact, the point of interaction, and of communication, that I am most interested in. Through the mediums of new media art and interaction design, I have attempted to reorder and play with the dialectics of networked space as being itself a medium for art. In order to uncover the grey area between the worlds that digital technologies create within and between us, as users and beings, I am making networked space my primary medium via the technologies which engineer it and which sustain its architecture.

The Internet as a Hyperobject

[the new scale of human affairs]

In Timothy Morton’s book Hyperobjects: Philosophy and Ecology after the End of the World, he coins the term “hyperobject” to refer to things that are “massively distributed in space and time relative to humans”. He goes on to say that “a hyperobject could be a blackhole, [or] the Lago Agrio oil field in Ecuador, [or] the Solar System, [or] the sum-total of all nuclear materials on Earth, [or] just plutonium, [or] the product of direct human manufacture, [or] just plastic bags”[7]. It follows that climate change is a hyperobject, or the erosion of the Louisiana swampland is a hyperobject. In all these examples, “local manifestations of the hyperobjects [are] not the hyperobjects themselves”[8]. By nature, then, hyperobjects are invisible, immaterial, things we cannot quite grasp, and yet “they can be detected in a space that consists of interrelationships between aesthetic properties of objects”[9].

The internet, then, can be qualified as a hyperobject. It manifests itself in a multiplicity of ways that make it seem familiar, accessible, and tangible. It is a place of memory making, of identity making, of creating a sense of belonging. Yet, if one were to ask someone what the internet is or where it is, one will more often than not offer quite a vague response. The internet is difficult to grasp and difficult to point at just like global warming or the speed of light. The internet “has no shape, […] has no face, just this name that describes everything and nothing at the same time”[10]. However, we seem to know that it is there, as though it is a place to go to, a reality that calls us in through signals and notifications. But is that enough to guarantee that it exists? We find ourselves at a dead end of cartesian thought. Cogito, ergo sum may no longer be supported within a context where the means of knowing extend the means of ‘existing’ things. For, “the internet does not exist” in itself, yet it does through its local manifestations of its infrastructure as a hyperobject[11]. The current malaise of the western world may best be explained by the extinction of one of its ontological pillars. As expresses Nam June Paik, “nowadays, Descartes would throw himself in the Seine in order to preserve his virginity of cognition”[12].

Virtual reality, as previously described in conjunction to physical reality, is therefore not a space in itself, but the sum of spaces created from the local manifestations of the hyperobject, the internet. The architecture of the internet is a systems architecture, like the roots of plants or the veins of the body. It is a network, and not a final destination. It is a circuit of routes with many junctions and stops where one is hypnotized by a sense of control in navigation. The point of entrance is a white light, and the point of exit is a black hole. It is a vacuum where physical “objects […] appear to become translucent and strangely compressed until they finally disappear altogether”[13]. Morton goes on to say that hyperobjects “generate space-time vortices, due to general relativity”[14]. As one receives a notification and instantly turns on the screen, one penetrates the depth of a mirror which has its own phenomenological properties separate from those of the physical scale, such that “things are themselves but we can’t point to them directly”[15]. When one decides to exit that virtual space which is locally manifested by the screen, or the notification, one then re-enters the appearing world of objects. One then decelerates from the speed of light. This new scale introduced by the medium of the internet makes it so that the “gap between phenomenon and thing yawns open, disturbing [ones] sense of presence and being in the world”, for in fact it is not a single scale that is introduced, but the tension created by cognitively incoherent scales of reality whose border is instantly traversable[16].

Fig. 2

c = 3 × 108 m/s (The Speed of Light)

The instantaneity of adaptation between different temporalities and spaces, facilitated by interactive interface technologies, does not allow consciousness to discern the border between them, but rather upholds a hybrid reality where virtual and real exist together. As the internet eliminates space, one is both there and not there. Pure duration is then ruptured, for pure duration is “the form taken by the succession of our inner states of consciousness when our self lets itself live, when it abstains from establishing a separation between the present state and anterior states”, or states that are not occurring in the same ‘location’[17]. Once, my therapist told me that the brain could not tell the difference between virtual events and real events, when trying to explain the mechanisms of chronic anxiety. The ontological experience of what is ‘here’, or what is offline, can be merged with the experience of things happening far away, or online, as they merge into the belief system of the mind. The local manifestations of the internet construct a ‘world’ space that is then experienced as a green screen, a flat surface whose depth is simulated, upon which we can appear or disappear, be simultaneously present and absent, via the diversion that the mind takes within the reality spectrum. It follows that this mind belongs to a body whose borders oscillate and twitch. Like in dreams, the narrative of everyday life is disjointed and incoherent, although emotionally and experientially believable, or held as ‘true’, within the architecture of the dreamscape. We can see ourselves from above and from within. Similarly, we can see the world from space and all angles – just like when one looks over the planet on Google Earth as one should be falling but instead hovers over the ‘world’ (whose original body is constantly updated and reimagined). This is a state of free fall, as Steyerl describes, because we are away from any gravity force. We are never really landing back to a firm ground upon which to base reality. She goes on to say that “this disorientation is partly due to the loss of a stable horizon, [and that] with the loss of a stable horizon also comes the departure of a stable paradigm or orientation, which has situated concepts of subject and object, of time and space, throughout modernity”[18]. If this is true of the subjective experience it may also be true in the formulation of culture. Like the speed of light, history as a collective narrative is compressed into a single simultaneous experience, resulting in its fragmentation and disorder, suggesting an alternative temporality altogether. Linear space and time as a cohesive movement within the fabric of reality has been replaced by the simultaneity of a multiplicity of perspectives and speeds, in the form of the rhizomatic structure of the internet. Mark Fisher describes this as a Cyberspace-time crisis, where one has to opt-out of cyberspace rather than opt in, imposing the internet’s parameters of space and of time[19]. Reality, for Fisher, is by definition “a form of collective dreaming” which, in the 21st century, is experienced through the stress between “the infinity of cyberspace” and “the finitude of the organism”[20]. Networked space is the space of reality and yet it is primarily characterized by an elimination of space altogether, precisely because it is infinite. This paradox is what makes it a hyperobject.

Steyerl makes the point that ‘reality’, or this consensual hallucination, is image, so much that “this means that one cannot understand reality without understanding cinema, photography, 3d modelling, animation, or other forms of moving or still image” for “image and world are […] just versions of each other”[21]. The green screen is a reality of postproduction, where “the world can be understood but also altered by its tools […] : editing, colour correction, filtering, cutting, and so on, […] as the means of creation of images and of the world in their wake”[22]. As we are eternally falling through images, reality flashes by to the point of blindness: “This is not simply white light. It is the result of too much information. Too much equates to nothing”[23]. Like in Sugimoto’s long exposure shots of cinemas, where “the architecture of the space is lit predominantly by the residual light of the erased film”, the architecture of our everyday life is predominantly lit by the residue of a succession of sensorial flashes at high speed, which cancel each other out, resulting in a void[24]. Even though falling entails movement, by virtue of it being eternal it is also stagnating. Virtual reality, as the texture of the green screen, can then be defined as “the removal of a single human shaped mass from the fabric of the universe”, for existing at the speed of light demands of us to not ‘exist’ at all[25]. Such as the Japanese Olympics of 2021 where stadiums were void of human beings due to the COVID pandemic, or such as Zuckerberg’s metaverse, suggesting that one needs to enter the virtual plane in order to exist, leaving whole cities void of human presence. Hyperobjects such as the internet, as Morton argues, have therefore brought about the end of the world: the world is left as a green screen[26].

Fig. 3

“Every desire

is an end

and every end

is a desire

then

the end of the world

is a desire of the world

what type of end do you desire?”

Sun Ra

Fig.4

Engineering the border between the virtual and the real

[designing containment: feedback loops as closed circuits]

The blurring of the border of what is obviously virtual and what is obviously real is grounded in the idea that reality is a spectrum. This is best illustrated by the following diagram where we can identify different degrees of reality. It goes from the ‘real world’ to ‘augmented reality’ (AR), to ‘augmented virtuality’ (AR), to ‘virtual reality’ (VR). All of these realities put together are identified as ‘mixed reality (MR)’[27].

Fig. 5

Fig. 6

This spectrum is actuated via interactive interface technologies. They are the point of contact between us and the abstract body of the internet, rendering the things that we can’t grasp somehow accessible and translatable to our minds. It is via their language that we have a shared sense of space in the embodied internet. As the brain cannot tell the difference between the virtual and the real, images or virtual events transcend us in the form of memory just like physical reality does. They include screens, sensors, cameras, 3D sound, machine learning, and so on. It follows that the interaction designers, engineers, and owners of the means of production of such interface technologies are those that determine the way in which we communicate with the immaterial and virtual world, or what Mark Fisher would call the “ghosts” of ourselves[28].

Interactive interfaces are asserted through their association to both progress (future) and endlessness. One can ask themselves what iPhone we are at in the same way one asks themselves what year it is. And yet at the same time, it is easier to imagine the end of the world than the end of capitalism in the same way that it is impossible to imagine the end of the iPhone (or other associated technologies of permanence). As such,

“endlessness can be seen as a culturally and ideologically manipulated phenomenon, when linked to and produced by technologies of modernity and capital that have vested interests in the mythological maintenance of their own structures as flexible forms of permanence”[29].

Even though interface technologies are products that we buy, they have also become the necessary means of communication and of societal participation. We are biopolitically policed in seemingly indiscernible ways, making the interests of surveillance bond with the economic interests of behavioural prediction, such as data mining. This form of policing, of establishing the impossibility of bypassing rules within a regulated virtual space, is biopolitical in the sense that it touches upon the realm of body and mind at a sensorial level because the internet is established as an ‘uninterrupted interface’, and therefore is “a perpetual test of the subject’s presence with his own objects”[30].

The trouble begins, as David Rokeby states, as soon “as the user’s awareness of the interface ends, in the true “Narcissus style of one hypnotized by the […] extension of his own being in a new technical form”[31]. In Rokeby’s web essay Transforming Mirrors, he offers a coherent explanation of how interactive technologies engineer containment within users and audiences. Through looking at their mechanisms, one can better understand how the world as a green screen, as flat and absent of depth, can simulate an illusion of depth and of consequentiality, thus hypnotizing the user. He compares interactive technology to mirrors, stating that a technology is interactive to the degree that “it reflects the consequences of our actions or decisions back to us”, thus providing us with a self-image[32]. A feedback system is therefore created between the re-action of the user and the mirroring of the interface, resulting in an echo and a simulation of depth within the flat surface.

In the Tibetan Book of the Dead (TBD), written in the 8th century AD, there is a passage entitled ‘awareness’, where synonyms for ‘mind’ are offered. Some of these include definitions such as “perfection of discriminate awareness”, or “expanse of reality”. In my own exploration of the ontological implications of Rokeby’s Mirrors, I decided to make ‘mirrors’ another synonym for ‘mind’. I then attributed interactive interface technologies with different definitions of mind offered by the TBD.

Fig. 7

The smartphone is a ‘pocket mirror’ that slides into one’s hand and which can be pulled out at any time, where one can be immersed in a dimensional virtual space through a flat surface. It is an object of “perfection of discriminate awareness” as the world that it contains has a strict system of segregation of modes of participation within social life and reality. It mirrors us and our sense of participation in the ‘world’. Equivalently, the evolution of AI is also a form of discriminate awareness, for it is trained to distinguish, and even emulate, objects of reality via truths or falsehoods. Therefore, AI replicates intelligence in an attempt to mirror the mind’s ability to differentiate reality (‘truth’) from what is not real (‘false’). Social media is a mirror in the sense that it is the realm of the self-image. It is a source of ‘diverse joys and sorrows of cyclical existence’, another definition by the TBD when describing the mind. These are just some ways in which interface technologies act as extensions of ourselves by virtue of mirroring the mind.

When the mind as mirror communicates with an interactive, mirroring, interface, it is the same as placing two mirrors in front of each other. Rokeby describes this phenomenon as a stereoscopic tension, whereby “the tension that exists between these two points of view is resolved by the brain into the revelation of depth”[33]. Like an echo endlessly repeating the same image, feedback is created via the closed-circuit system of mirroring interaction and validating the original image of world. As Nam June Paik states, “[feedback] is the bread and butter of electronic culture” and it “never occurs in an open circuit: closed cycle is the unconditional pre-requisite for this happening”[34]. As such, as each person sees himself as “an astronaut in his capsule”, reality inside the bubble is made up of closed circuits and feedback systems that create an illusion of depth, of dimension, of consequentiality, of ‘being there’. The engineering of this simulated depth is what sustains the mind in an uninterrupted hypnotic state where the virtual and the real meet, and where the tension is resolved. When two mirrors meet, the image of infinity unfolds, but it is nonetheless nothing more than an image. Even if you try to jump into the open space offered by the mirror, you will still hit your head against a wall. As such, interactive technologies act as mirrors that create feedback loops which create white noise – like when there is sound feedback and the sound replicating itself accumulates to an endlessly high pitch, or like when two cameras face each other and the colour spectrum accumulates to create an infinitely white square. Too much equates to nothing, resulting in “the active assembly of nobody in order to see nothing”[35].

In an attempt to explore this ‘magic trick’, I used a now widespread interactive interface and communication technology on another living being: Zoom. Zoom is an interactive interface that flourished as a consequence of crisis and is culturally associated to crisis. In fact, the ‘world’ as we know it, still in the midst of COVID-19, is a world where zoom is widespread as a communications technology. I had never heard of zoom prior to this crisis (which turned out to be used as a surveillance technology). What Zoom reveals is what Steven Shaviro argues in his essay on accelerationist aesthetics, namely that “crises do not endanger the capitalist order”, rather they help it, “phoenix-like”, to renew itself[36]. In this sense, the capitalist technocracy is renewed via another form of perceptive subversion.

With this in mind, I created a zoom call between four devices whose cameras and microphones were all pointed at a pig. The devices ‘spoke’ to each other via the feedback created from the sounds of the pig. What happened was that the pig actually held its head up to listen to this sound that it kept hearing, as though there was something there. Rummaging around and smelling around, whenever the feedback got loud enough it would stay still, as though asking ‘who is there?’. But what was there was just the pig itself.

Fig. 8

Interactive technologies engineer containment in exactly that way: by creating the illusion of something ‘being there’ when in fact it is only the reflection of ourselves. Or it is that we gravitate towards erasing ourselves in order to establish that we exist. As such, we travel in a simulation of time, of movement, of self-realization, when in fact the world we are referring to as exterior to ourselves is just the traces of ourselves that we leave behind. Zuckerberg encourages the perpetuation of his empire in a celebration of the ingenious invention of the metaverse by saying that “you’re actuallyinside the experience, not just looking at it”, as if physical reality couldn’t already offer us that possibility[37]. And yet what is important to remember is that “there is no absolute absence, only presences made of different substances and consistencies”[38].

Art: a glitch in the screen – Digital Anarchitecture

Poor images, low-fi content, digital junk, errors leading to alternative and autonomous spaces – my medium is grey matter, a bridge between light and absence of light, a fog, a blur, no resolution, no depth. If there was a ZAD[39]on / in the internet, what would it look, feel, smell, sound like?

First, to establish that it is all real. It is not just a question of articulating the virtuality of the internet as a hyperobject that one should then think that it isn’t real. It is just that the terms to reality no longer apply in the same way. As Morton states, “for all humans as we transition into this age of asymmetry, there are real things for sure, just not as we know them or knew them”[40].

Right: Fig. 10

Digital space is not a smooth surface. In fact, it is often prone to errors, to crevices, to possibilities of diversion. It is first crucial to understand its mechanisms in the same way that it is crucial to become aware of the interface in order to realize its flatness. As Rokeby states, the interactive artists “holds a mirror to the spectator” in order for the spectator to become aware of themselves. The interactive artist is akin to the description of Tehshing Hsieh in his year long performance whereby he becomes “a body lacking temporal continuity and physical integrity, a body whose borders oscillate and twitch, yet whose gaze in the ruins of visibility, holds its observer remorselessly in its grip, as if to say it is you I am implicating here”[41].

In a few of my own video works I have often played with first person perspective, similarly to video games. I have documented and staged the subjective experience of contemporary life through its task-performing movement, individualized isolation and interpretation of reality. In a video that I called Ocean, I placed a GoPro on myself and followed a group of people into the sea. This is an interactive video work, whereby the image reacts to sound. The sound piece is glitchy and ambient and uses the rhythms of the waves and the underwater soundscape to equate the sensation of drowning to the sensation of losing ground. As the video plays, the image distorts itself according to the sound. And thus, it feels as though the protagonist, who is paralleled to the spectator, is (are) drowning in the mass of a spatial glitch.

Fig. 11

I have always had an aesthetic attraction towards low quality digital images. When watching video footage of 9/11 on camcorders, I couldn’t help but feel a parallel between some of the low-quality images of catastrophe with the images of drowning in my Ocean video piece. It seems that in both cases, these are documentations of an obliteration of time and space, or of ‘world’. As Steyerl describes in her Defense of the Poor Image, “poor images […] express a condition of dematerialization”[42]. In the 9/11 documentation, it is as if this specific frame is the image of the end of history, or the western world. In the Ocean video, it is also a scene of time and space ending.

Fig. 12

It is not so much the aspect of catastrophe that becomes important, but the texture of reality falling apart – or to reveal what reality is made of. When the seemingly permanent textures of reality reveal themselves as fragile, vulnerable, and prone to mistakes, one may break away from the hypnotic assumption that these structures are indestructible. In a practice of digital anarchitecture[43], one may claim power over the ways in which the networked space is dictated, constructed, and how it travels through us. This first begins with awareness. No one or nothing is in total control over an outcome, like in code, where you may give a set of rules to follow which may generatively create something completely unexpected. That technologies may bare within their mechanisms space for improvisation and chance, and therefore offer a means to assert “inassimilable values” to an otherwise perfectly ordered and predictable world. Like in age old drum patterns, where polyrhythms merge together to create rich and multi-layered music, one then discovers that out of something simple is born something so complex and alive. In asserting that digital space is a medium for art one asserts that it cannot be ignored or separated from anything called ‘reality’. In asserting that digital space is real, one can become more aware of the interface that they are a part of and interact with. By claiming an awareness over one’s sensorial experience of living, one can then finally confront the seemingly immaterial texture of reality that surrounds and penetrates them. One can orient themselves again in space, with depth. One can finally see again.

Fig. 13

Conclusion

In this critical journal, I have attempted to articulate the ways in which we experience reality when digital technologies are blended within all of its dimensions. In an acknowledgement of this digital reality, which is chronically changing faster than I may be able to describe, I have illustrated the mechanisms through which contemporary technologies work, and through which they dominate our sensorial landscapes. As a result, I have articulated some of my own reflections upon the matter as a means to give shape to the seemingly immaterial. I have established that digital space is a space which can be occupied by virtue of it occupying us, in the same way that physical space can be disputed, transformed, and reimagined. I am not so much offering a solution, but rather an alternative way of seeing, one which may best allow to remain aware and sensitive to the rapidly evolving textures of everyday life. First and foremost, to acknowledge that it is real, and that it is happening right now.

[1] Bubble Vision. 2018. [video] H. Steyerl. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=T1Qhy0_PCjs.

[2] About.facebook.com. 2021. Welcome to Meta | Meta. [online] Available at: <https://about.facebook.com/meta?utm_source=Google&utm_medium=paid-search&utm_campaign=metaverse&utm_content=post-launch> [Accessed 2 November 2021].

[3] McLuhan, M. and Gordon, W., 2015. Understanding Media. Berkeley, Calif.: Gingko Press, p.8.

[4] Morton, T., 2017. Hyperobjects. Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press, p.3

[5] Steyerl, H. and Aikens, N., 2014. Too Much World: Is the Internet Dead?. Berlin: Sternberg, p.1.

[6] McLuhan, M. and Gordon, W., 2015. P 7.

[7] Morton, T., 2017. P.1

[8] Morton, T., 2017. P.1

[9] Morton, T., 2017. P.1

[10] 2015. The Internet Does Not Exist. Sternberg Press (e-flux journals), p.7.

[11] 2015. The Internet Does Not Exist. Sternberg press (e-flux), p.1

[12]2019. We Are in Open Circuits : Writings by Nam June Paik. MIT Press, p.279.

[13]Morton, T., 2017. P.11

[14] Morton, T., 2017. P.11

[15] Morton, T., 2017. P.11

[16]Morton, T., 2017. P.12

[17] Hsieh, T. and Heathfield, 2008, A., n.d. Out of now - the lifeworks of Tehching Hsieh. MIT press, p.21

[18]Steyerl, H. and Berardi, F., n.d. Free fall. e-flux journals. P.4

[19]Mark Fisher - Cybertime Crisis. 2020. [video] https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=zOQgCg73sfQ: Mark Fisher Cyberfield.

[20] Mark Fisher - Cybertime Crisis. 2020. [video]

[21] Steyerl, H. and Aikens, N., 2014. p.6.

[22] Steyerl, H. and Aikens, N., 2014. p.6.

[23] Hsieh, T. and Heathfield, 2008, p.33

[24]Hsieh, T. and Heathfield, 2008, p.33

[25]Bubble Vision. 2018. [video] H. Steyerl.

[26] Morton, T., 2017, p.2

[27] Gupta, V., 2021. Preparing for a New Reality: Augmented and Virtual Reality. [online]

[28] Fisher. M., 2009. Capitalist Realism: Is there no alternative? Winchester: O Books. P.13

[29] Hsieh, T. and Heathfield, 2008, p.33

[30] Baudrillard, J., 1997. The Ecstasy of Communication. P.127

[31] McLuhan, M. and Gordon, W., 2015. p.14.

[32] Rokeby, D., 2021. David Rokeby : Transforming Mirrors. [online] Davidrokeby.com. Available at: <http://www.davidrokeby.com/mirrorsintro.html> [Accessed 3 November 2021].

[33] Rokeby, D., 2021. David Rokeby : Transforming Mirrors. [online].

[34] 2019. We Are in Open Circuits : Writings by Nam June Paik. MIT Press, p.301.

[35] Hsieh, T. and Heathfield, 2008, p.35

[36] Shaviro, S., 2015. No speed limit. Minneapolis: University of Minnesota press. P.42

[37] About.facebook.com. 2021. Welcome to Meta | Meta. [online]

[38] Hsieh, T. and Heathfield, 2008, p.37

[39] Zone à Défendre (Zone to Defend) – French experession that refers to the autonomously occupied zone of Notre-Dame-des-Landes in France. According to the dictionary, it is defined as an “area whose development is planned for an alternative period” (feminine).

[40] Morton, T., 2017, p.2

[41] Hsieh, T. and Heathfield, 2008,p.35

[42] 2013. Hito Steyerl. The wretched of the screen. New York: Sternberg Press. P.40

[43] In reference to artist Gorden Matta-Clark, who coined the term anarchitecture, most known for his radical interventions on abandoned buildings, reshaping and cutting through their physical structures.

List of Illustrations

Fig.1: Magritte, R., 1936. la Clef des Champs. [Oil on canvas].

Fig. 2: Rafman, J., 2008. 9-eyes. [Google Street View].

Fig. 3: Sugimoto, H., 2014. Teatro dei Rozzi, Siena "Summer Time". [Analog Film Photograph].

Fig. 4: All That's Interesting. 2019. Inside The Ghost Cities Of China That Feel Like An Eerie, Futuristic Dystopia. [online] Available at: <https://allthatsinteresting.com/chinese-ghost-cities> [Accessed 13 January 2022].

Fig. 5: Gupta, V., 2021. Preparing for a New Reality: Augmented and Virtual Reality. [online]

Fig. 6: Gupta, V., 2021. Preparing for a New Reality: Augmented and Virtual Reality. [online]

Fig.7: Lene de Montaigu, 2020. Synonyms for Mind. [ink on paper]

Fig. 8: Lene de Montaigu, 2020. Zoom 92212838368. [video]

Fig. 9: Magritte, R., 1936. la Clef des Champs. [Oil on canvas].

Fig. 10: Steyerl, H., 2010. STRIKE.

Fig. 11: Lene de Montaigu, 2020. Océan. [video]

Fig. 12: N.J. Burkett reporting as Twin Towers begin to collapse on September 11, 2001. 2001. [video] https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=oCPVNLLo-mI: Eyewitness News ABC7NY.

Fig. 13: Matta-Clark, G., 1975. Conical Intersect. [Black and White Photograph].